Coding styles: A personal preference or bad practice?

Vinicius Monteiro

October 22, 2021

We all have different styles and preferences in everything in life, including how we write code.

Imprinting your personality in the code brings originality and a sense of ownership and responsibility It’s essential to keep us motivated, and it makes us feel good (at least I do). However, is one’s coding style always just a harmless style? Or does it impact readability and hence maintenance?

This has been on my mind a lot lately. For instance, during a code review, I often question whether I should bring specific ways of coding into the discussion or not. How does it affect the application; Is it readable, is it easy to maintain?

Or perhaps I should leave it alone, thinking to myself — Don’t be picky, it’s just their preference, it’s not a matter of right or wrong.

Identifying a programmer’s fingerprint

We could say a developer has a coding identity or ‘fingerprint’, similar to what happens with regular writing. When writing, there is often a pattern with which someone writes — the terms, vocabulary, structure. A linguistic expert, for instance, can identify the author of some anonymous material simply by analyzing these patterns.

Analizing these patterns can even tell things such as the age and place of birth of the author. This technique is called Stylometry. It’s even used in criminal investigations. Machine learning algorithms are used for Stylometry as well — as they can process many texts/books and identify patterns.

We probably can’t tell who committed a crime based on the coding style (can we?). But, let’s say in a team of ten developers, if there are no strict standards to follow, I believe it’s possible to identify who wrote a code block without looking at the author information.

In this post, I’ll list a number of different ways of writing code I’ve encountered throughout my career as a Software Engineer. I’ll focus mostly on Java, but some things are applicable in general.

I’ll also offer my perspective on whether it is just a coding preference that we shouldn’t care about, or if perhaps there is a right (and wrong) way of doing it.

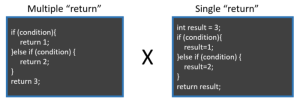

Multiple or single “returns”

One coding practice that tends to reflect a developer’s preference is the use of a single or multiple ‘returns’.

I used to prefer a single ‘return’ at the end of the method, and I still do this sometimes. But more recently, I find that I tend to return where the condition satisfies — I think it’s easier to maintain (it looks uglier, though). You’re more sure of when the method returns a particular value, and you can be certain that any code after the return won’t be executed.

Otherwise, you need to read every if-else or break inside a loop. Often the logic is not as simple as the one presented above.

If I see some complex logic with multiple if-else conditions chained together, mixed with ‘break’ inside loops, etc., and one single return at the end, when a particular value could’ve been returned before — I’d explain my perspective and see if the person agrees with doing the change. However, I wouldn’t push it too much and be picky about it. It’s a subtle benefit that may be hard to convey.

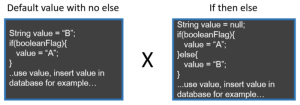

To Else or not?

Another variation I tend to see is whether the coder uses the Else statement. Is it really necessary? I commonly do the version on the left — “Default value with no else” when it’s a simple variable assignment case. It just feels cleaner to me.

A counter-argument could be that the first example uses fewer resources, because you start with null, and only one value (A or B) is assigned at max. On the other hand, a maximum of two variable assignments could happen (if booleanFlag is true). I’d agree with that, but not for all cases. Setting a default first would be fine. It depends on what is being executed as the ‘default’.

This example was one ‘challenge’ that my Bachelor course coordinator threw at us newbies in the first semester during a programming class — “How could you rewrite the first version in fewer lines?!”

No one in the class could answer it. Everyone was still coming to terms with the fact that the course wasn’t really about learning Microsoft Office.

Although I prefer the second version (for a simple variable assignment), I’d probably not bring it up to discuss or ask to change in a code review.

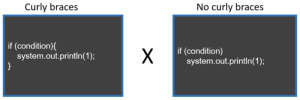

Curly braces or not

Curly braces are used to delimit the start and end of a block of code. Curly braces become ‘optional’ when only one statement is inside an IF condition, a While or For loop.

Both code snippets do the same thing; there is no difference functionality wise. Which one do you prefer?

For me, I’m totally in favour of using curly braces, always. It shouldn’t be optional. I think that mainly because, in languages like Java, the indentation doesn’t drive what will be executed as part of the if condition or loop (for Python, it does, for example). Indentation only, without curly braces, cannot be relied on — it may trick you into thinking that something will be executed (or won’t be executed) when it won’t (or when it will).

So NOT using curly braces may lead to hidden bugs and bad readability in general. In contrast, using it leaves no room for doubt on which line will run or not. It becomes easier to maintain, in my view.

Here are some examples to help illustrate what I mean:

if (count > 10) System.out.println(1); System.out.println(2); System.out.println(3);When you read the code above, you think all three lines will be executed if the condition satisfies. But it’s not true. There are no curly braces; hence only one will be printed if, let’s say, the count is equal to eleven. Two and three will be printed in any case, even if, for example, the count is five.

Another example:

int count=15; if (count > 10) if (count > 20) return 1; else return 2; return 3;The else is aligned with the first if condition, but it’s instead part of the if condition just before. The program returns two as the count is less than twenty.

In a code review, I would probably ask to change it (very politely and diplomatically, of course). The other team member may prefer without curly braces and depending on my position, that’s fine — I wouldn’t push it too much.

Checked or unchecked exception

Exceptions are events that happen outside of the normal flow. It allows programmers to separate the code that deals with the success path from those that deal with errors.

Java has its Exception classes, or the developer can create its own by extending Exception or RuntimeException.

Let’s say there is some particular error validation related to your business. You could create a class, for example, ProductNotFoundException, that extends the Exception class.

Another characteristic of how exceptions in Java work is that there are two types of exceptions: Checked and Unchecked.

Checked exceptions are exceptions that extend the Exception class. Their behaviour is: If a code inside method A throws a checked exception, any method that calls method A must handle the checked exception by either catching or throwing (or perhaps both). The code will not compile otherwise. Extending a Checked exception is a way to force programmers to handle a specific error.

Unchecked exceptions are used for unrecoverable errors. Such errors are not to be handled. Instead, programmers should tackle the root cause that triggers them. Example: NullpointerException.

These exceptions extend RuntimeException, and are different from Checked ones. The caller method is not enforced to handle it by catching or throwing it.

Despite being used for unrecoverable errors, one could create an Unchecked exception. It’s just a matter of extending RuntimeException.

Any method can handle such exceptions, but the compiler doesn’t complain if they don’t. That means that you can have the exception handling code only where it is needed.

I learned and used to code by always using Checked exceptions. You probably learned that way too. If you implement a method that calls another method A that generates a checked error, the compiler will tell you that you need to do something about it. And the intent of who created method A was exactly that, to alert and force others to handle the error.

Oracle does recommend always using a Checked exception if you expect to recover from the error. https://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/essential/exceptions/runtime.html

Here’s the bottom line guideline: If a client can reasonably be expected to recover from an exception, make it a checked exception. If a client cannot do anything to recover from the exception, make it an unchecked exception.

I admit that despite Oracle’s recommendation and being a good practice to use Checked exceptions, I have extended RuntimeException before. I understand that throwing exceptions should be considered just as essential as the method’s parameters and return value; it’s part of the method programming interface.

But, no one creates a method that receives a parameter and does nothing with it. I find that throwing it, and re-throwing it upstream without doing any meaningful handling (log, return message to the user), creates a bit of clutter. It’s unnecessary.

With unchecked exceptions, only the method that generates the error and the one that handles it needs to deal with it. It’s a calculated risk I choose to take sometimes. It’s a calculated risk in the sense that an error that is supposed to be handled may not be — another developer that calls your method won’t be alerted by the compiler to handle the exception that your method raises. It’s a drawback from making it Unchecked, that’s why is considered a bad practice in general.

If I see that one of the team members chose to create and use an Unchecked exception, I would probably want to know the thought process and make sure they know the pros and cons.

Using an If then versus an Else exception

Another thing programmers tend to differ on is the use of an If then exception when an Else exception would also work.

I’ve experimented with both ways throughout my career as a developer. Today I prefer the version on the right — “If then exception”. I see it as clearer — easier to read where errors are generated. And I usually have it aside from the main logic in a private ‘validate’ method.

I would probably try to change in a code review if one of my peers uses the second version. Unless the code is as simple as the example in this section — then I’d leave it (maybe).

Positioning the curly braces

This one is just cosmetics. It’s silly. It’s like preferring a toast cut diagonally versus horizontally or vertically (You’re probably wondering — How can someone not choose diagonally?! Anyway…).

I find it funny that, even in things like this, people have preferences.

I prefer the first one, with curly braces in the same line as if condition or loop. I don’t see any considerable benefit of one or the other. I would not ask another programmer to change it.

Final thoughts

Certain coding style choices are personal, with no benefit or cons over others. It’s like preferring blue to red, orange to apple.

However, some other preferences are more arguable — does it make the code less readable or error-prone? Out of the stylistic differences I covered, the no use of curly braces and checked versus unchecked exception examples stand out. These are the ones with the most impact.

Even if there are coding standards set in place, it’s probably best if they aren’t too rigid. One still needs to allow the developer a certain amount of leeway to make their own personal mark. If it were up to me, I would set a rule to always use curly braces and, possibly, to use checked exceptions (because it tends to be safer), but that’s about it. In the end, it should be discussed and agreed upon as a team.